JANET GEDDES IN ST GILES’ CHURCH, EDINBURGH

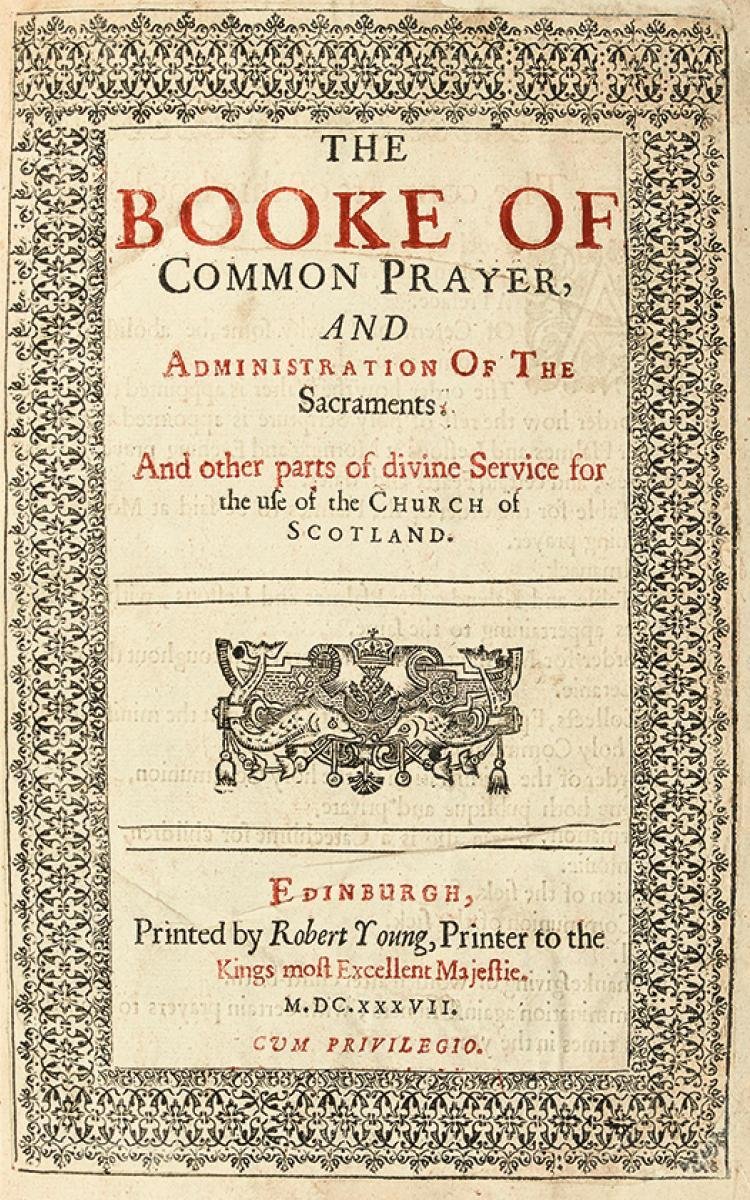

Let me tell you a story. The year was 1637. On Sunday, July 23, at St. Giles’ Cathedral in Edinburgh, a service began that used a new liturgy for the first time. “The Booke of Common Prayer and Administration Of The Sacraments: And other parts of divine Service for the use of the Church of Scotland” had been compiled at the instruction of King Charles I for use in Scotland. Its imposition by the crown was not, shall we say, universally popular. At that first service, a woman named Jenny Geddes allegedly threw a stool at James Hannay, the Dean of Edinburgh, as he began to pray the collects. She was said to have exclaimed "De’il gie you colic, the wame o’ ye, fause thief; daur ye say Mass in my lug?" meaning “Devil cause you colic in your stomach, false thief: dare you say the Mass in my ear?”

This act started a cascade of events that would shake kingdoms. The congregation began hurling Bibles and furniture, and shouting abuse at the Dean as well. Rioting broke out in the streets and spread to other cities. Charles I refused to compromise on the use of Anglican liturgy, and in 1638 his opponents in Scotland signed a document called the National Covenant to oppose both the Prayer Book and the role of bishops in church governance. Then, in 1639, the King sent troops to suppress the rebellion started by the Covenanters’ movement. The “Bishops’ War” that followed would lead in time to both the Irish Rebellion and the English Civil War, and finally to the execution of the King.

When Cromwell and the Puritan Parliament took over, they attempted to suppress Prayer Book worship, not always with success. Some priests memorized parts of the 1559 Prayer Book and recited them under the guise of extemporaneous prayer. Others used the Prayer Book privately for occasions like family baptisms.

Then, in 1660, King Charles II was restored to the throne. A new Prayer Book was commissioned, a mild revision of the 1559 book that was intended to steer a peace-preserving ‘middle way’ in its flexibility: “It hath been the wisdom of the Church of England, ever since the first compiling of her public Liturgy to keep the mean between two extremes, of too much stiffness in refusing, and of too much easiness in admitting any variation from it,” the Preface states. The 1662 Prayer Book became the standard liturgy not only in the Church of England, but in many other parts of the world where English missionaries traveled. It remains the authorized Prayer Book of the Church of England, although there is a supplemental 20th century book called Common Worship that provides rites equivalent to our Rite II liturgy.

On Sunday, October 30, at 5pm, we will remember this heritage of prayer and worship with a 1662 Book of Common Prayer service. We are fortunate to have Drew Keane, an expert in the 1662 liturgy, consulting with us to help us structure the service as it would have been done in the late 1600s. We aren’t doing this as merely a historical curiosity, but rather as a way to discover how the “habits of the heart” practiced by Anglicans more than 300 years ago are so close to our own — and why they have lasted.

Won’t you join us?

Yours in Christ,

The Rev. Cn. Dr. Kara N. Slade, Associate Rector